Систематической погрешностью называется составляющая погрешности измерения, остающаяся постоянной или закономерно меняющаяся при повторных измерениях одной и той же величины. При этом предполагается, что систематические погрешности представляют собой определенную функцию неслучайных факторов, состав которых зависит от физических, конструкционных и технологических особенностей средств измерений, условий их применения, а также индивидуальных качеств наблюдателя. Сложные детерминированные закономерности, которым подчиняются систематические погрешности, определяются либо при создании средств измерений и комплектации измерительной аппаратуры, либо непосредственно при подготовке измерительного эксперимента и в процессе его проведения. Совершенствование методов измерения, использование высококачественных материалом, прогрессивная технология — все это позволяет на практике устранить систематические погрешности настолько, что при обработке результатов наблюдений с их наличием зачастую не приходится считаться.

Систематические погрешности принято классифицировать в зависимости от причин их возникновения и по характеру их проявления при измерениях.

В зависимости от причин возникновения рассматриваются четыре вида систематических погрешностей.

1. Погрешности метода, или теоретические погрешности, проистекающие от ошибочности или недостаточной разработки принятой теории метода измерений в целом или от допущенных упрощений при проведении измерений.

Погрешности метода возникают также при экстраполяции свойства, измеренного на ограниченной части некоторого объекта, на весь объект, если последний не обладает однородностью измеряемого свойства. Так, считая диаметр цилиндрического вала равным результату, полученному при измерении в одном сечении и в одном направлении, мы допускаем систематическую погрешность, полностью определяемую отклонениями формы исследуемого вала. При определении плотности вещества по измерениям массы и объема некоторой пробы возникает систематическая погрешность, если проба содержала некоторое количество примесей, а результат измерения принимается за характеристику данного вещества -вообще.

К погрешностям метода следует отнести также те погрешности, которые возникают вследствие влияния измерительной аппаратуры на измеряемые свойства объекта. Подобные явления возникают, например, при измерении длин, когда измерительное усилие используемых приборов достаточно велико, при регистрации быстропротекаюших процессов недостаточно быстродействующей аппаратурой, при измерениях температур жидкостными или газовыми термометрами и т.д.

2. Инструментальные погрешности, зависящие от погрешностей применяемых средств измерений.. Среди инструментальных погрешностей в отдельную группу выделяются погрешности схемы, не связанные с неточностью изготовления средств измерения и обязанные своим происхождением самой структурной схеме средств измерений. Исследование инструментальных погрешностей является предметом специальной дисциплины — теории точности измерительных устройств.

3. Погрешности, обусловленные неправильной установкой и взаимным расположением средств измерения, являющихся частью единого комплекса, несогласованностью их характеристик, влиянием внешних температурных, гравитационных, радиационных и других полей, нестабильностью источников питания, несогласованностью входных и выходных параметров электрических цепей приборов и т.д.

4. Личные погрешности, обусловленные индивидуальными особенностями наблюдателя. Такого рода погрешности вызываются, например, запаздыванием или опережением при регистрации сигнала, неправильным отсчетом десятых долей деления шкалы, асимметрией, возникающей при установке штриха посередине между двумя рисками.

По характеру своего поведения в процессе измерения систематические погрешности подразделяются на постоянные и переменные.

Постоянные систематические погрешности возникают, например, при неправильной установке начала отсчета, неправильной градуировке и юстировке средств измерения и остаются постоянными при всех повторных наблюдениях. Поэтому, если уж они возникли, их очень трудно обнаружить в результатах наблюдений.

Среди переменных систематических погрешностей принято выделять прогрессивные и периодические.

Прогрессивная погрешность возникает, например, при взвешивании, когда одно из коромысел весов находится ближе к источнику тепла, чем другое, поэтому быстрее нагревается и

удлиняется. Это приводит к систематическому сдвигу начала отсчета и к монотонному изменению показаний весов.

Периодическая погрешность присуща измерительным приборам с круговой шкалой, если ось вращения указателя не совпадает с осью шкалы.

Все остальные виды систематических погрешностей принято называть погрешностями, изменяющимися по сложному закону.

В тех случаях, когда при создании средств измерений, необходимых для данной измерительной установки, не удается устранить влияние систематических погрешностей, приходится специально организовывать измерительный процесс и осуществлять математическую обработку результатов. Методы борьбы с систематическими погрешностями заключаются в их обнаружении и последующем исключении путем полной или частичной компенсации. Основные трудности, часто непреодолимые, состоят именно в обнаружении систематических погрешностей, поэтому иногда приходится довольствоваться приближенным их анализом.

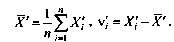

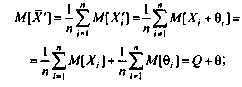

Способы обнаружения систематических погрешностей. Результаты наблюдений, полученные при наличии систематических погрешностей, будем называть неисправленными и в отличие от исправленных снабжать штрихами их обозначения (например, Х1, Х2 и т.д.). Вычисленные в этих условиях средние арифметические значения и отклонения от результатов наблюдений будем также называть неисправленными и ставить штрихи у символов этих величин. Таким образом,

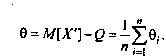

Поскольку неисправленные результаты наблюдений включают в себя систематические погрешности, сумму которых для каждого /-го наблюдения будем обозначать через 8., то их математическое ожидание не совпадает с истинным значением измеряемой величины и отличается от него на некоторую величину 0, называемую систематической погрешностью неисправленного среднего арифметического. Действительно,

Если систематические погрешности постоянны, т.е. 0/ = 0, /=1,2, …, п, то неисправленные отклонения могут быть непосредственно использованы для оценки рассеивания ряда наблюдений. В противном случае необходимо предварительно исправить отдельные результаты измерений, введя в них так называемые поправки, равные систематическим погрешностям по величине и обратные им по знаку:

q = -Oi.

Таким образом, для нахождения исправленного среднего арифметического и оценки его рассеивания относительно истинного значения измеряемой величины необходимо обнаружить систематические погрешности и исключить их путем введения поправок или соответствующей каждому конкретному случаю организации самого измерения. Остановимся подробнее на некоторых способах обнаружения систематических погрешностей.

Постоянные систематические погрешности не влияют на значения случайных отклонений результатов наблюдений от средних арифметических, поэтому никакая математическая обработка результатов наблюдений не может привести к их обнаружению. Анализ таких погрешностей возможен только на основании некоторых априорных знаний об этих погрешностях, получаемых, например, при поверке средств измерений. Измеряемая величина при поверке обычно воспроизводится образцовой мерой, действительное значение которой известно. Поэтому разность между средним арифметическим результатов наблюдения и значением меры с точностью, определяемой погрешностью аттестации меры и случайными погрешностями измерения, равна искомой систематической погрешности.

Одним из наиболее действенных способов обнаружения систематических погрешностей в ряде результатов наблюдений является построение графика последовательности неисправленных значений случайных отклонений результатов наблюдений от средних арифметических.

Рассматриваемый способ обнаружения постоянных систематических погрешностей можно сформулировать следующим образом: если неисправленные отклонения результатов наблюдений резко изменяются при изменении условий наблюдений, то данные результаты содержат постоянную систематическую погрешность, зависящую от условий наблюдений.

Систематические погрешности являются детерминированными величинами, поэтому в принципе всегда могут быть вычислены и исключены из результатов измерений. После исключения систематических погрешностей получаем исправленные средние арифметические и исправленные отклонения результатов наблюдении, которые позволяют оценить степень рассеивания результатов.

Для исправления результатов наблюдений их складывают с поправками, равными систематическим погрешностям по величине и обратными им по знаку. Поправку определяют экспериментально при поверке приборов или в результате специальных исследований, обыкновенно с некоторой ограниченной точностью.

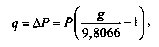

Поправки могут задаваться также в виде формул, по которым они вычисляются для каждого конкретного случая. Например, при измерениях и поверках с помощью образцовых манометров следует вводить поправки к их показаниям на местное значение ускорения свободного падения

где Р — измеряемое давление.

Введением поправки устраняется влияние только одной вполне определенной систематической погрешности, поэтому в результаты измерения зачастую приходится вводить очень большое число поправок. При этом вследствие ограниченной точности определения поправок накапливаются случайные погрешности и дисперсия результата измерения увеличивается.

Систематическая погрешность, остающаяся после введения поправок на ее наиболее существенные составляющие включает в себя ряд элементарных составляющих, называемых неисключенными остатками систематической погрешности. К их числу относятся погрешности:

• определения поправок;

• зависящие от точности измерения влияющих величин, входящих в формулы для определения поправок;

• связанные с колебаниями влияющих величин (температуры окружающей среды, напряжения питания и т.д.).

Перечисленные погрешности малы, и поправки на них не вводятся.

5.1. Систематические погрешности и их классификация

В

настоящее время, особенно после введения

одного из основополагающих метрологических

стандартов — ГОСТ 8.009-84 ТСИ. Нормируемые

метрологические характеристики средств

измерений», понятие «систематическая

погрешность» несколько изменилось

по отношению к определению, данному

ГОСТ 16263-70 ТСИ. Метрология. Термины и

определения». Систематическая

погрешность считается специфической,

«вырожденной» случайной величиной,

обладающей некоторыми, но не всеми

свойствами случайной величины, изучаемой

в теории вероятностей и математической

статистике. Свойства систематической

погрешности, которые необходимо

учитывать при объединении составляющих

погрешности,

отражаются такими же характеристиками,

что и свойства «настоящих» случайных

величин —

дисперсией (СКО) и коэффициентом взаимной

корреляции.

Систематическая

погрешность представляет собой

определенную функцию влияющих факторов,

состав которых зависит от физических,

конструктивных и технологических

особенностей СИ, условий их применения,

а также индивидуальных качеств

наблюдателя. В метрологической практике

при оценке систематических погрешностей

должно учитываться влияние следующих

основных факторов:

1.

Объект измерения. Перед измерением он

должен быть достаточно хорошо изучен

с целью корректного выбора его модели.

Чем полнее модель соответствует

исследуемому объекту, тем точнее могут

быть получены результаты измерения.

Например, кривизна земной поверхности

может не учитываться при измерении

площади сельскохозяйственных угодий,

так как она не вносит ощутимой погрешности,

однако при измерении площади океанов

ею пренебрегать уже нельзя.

2.

Субъект измерения. Его вклад в погрешность

измерения необходимо уменьшать путем

подбора операторов высокой квалификации

и соблюдения требований эргономики

при разработке СИ.

3.

Метод и средство измерений. Чрезвычайно

важен их правильный выбор, который

производится на основе априорной

информации об объекте измерения. Чем

больше априорной информации, тем точнее

может быть проведено измерение. Основной

вклад в систематическую погрешность

вносит, как правило, методическая

погрешность.

4.

Условия измерения. Обеспечение и

стабилизация нормальных условий

являются необходимыми требованиями

для минимизации дополнительной

погрешности, которая по своей природе,

как правило, является систематической.

Систематические

погрешности принято классифицировать

по двум признакам. По характеру

изменения во времени они

делятся на постоянные и переменные.

Постоянными

называются

такие погрешности измерения, которые

остаются неизменными в течение всей

серии измерений. Например, погрешность

от того, что неправильно установлен

ноль стрелочного электроизмерительного

прибора, погрешность от постоянного

дополнительного веса на чашке весов и

т.д. Переменными

называются

погрешности, изменяющиеся в процессе

измерения. Они делятся на монотонно

изменяющиеся, периодические и изменяющиеся

по сложному закону. Если в процессе

измерения систематическая погрешность

монотонно возрастает или убывает, ее

называют монотонно

изменяющейся. Например,

она имеет место при постепенном разряде

батареи, питающей средство измерений.

Периодической,

называется

погрешность, значение которой является

периодической функцией времени. Примером

может служить погрешность, обусловленная

суточными колебаниями напряжения

силовой питающей сети, температуры

окружающей среды и др. Систематические

погрешности могут изменяться и по более

сложному закону, обусловленному

какими-либо внешними причинами.

По

причинам

возникновения погрешности

делятся на методические, инструментальные

и личные (субъективные). Эти погрешности

подробно рассмотрены в разд. 4.1.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Систематическая погрешность (или, на физическом жаргоне, систематика) характеризует неточность измерительного инструмента или метода обработки данных. Если точнее, то она показывает наше ограниченное знание этой неточности: ведь если инструмент «врет», но мы хорошо знаем, насколько именно, то мы сможем скорректировать его показания и устранить инструментальную неопределенность результата. Слово «систематическая» означает, что вы можете повторять какое-то измерение на этой установке миллионы раз, но если у нее «сбит прицел», то вы систематически будете получать значение, отличающееся от истинного.

Конечно, систематические погрешности хочется взять под контроль. Поскольку это чисто инструментальный эффект, ответственность за это целиком лежит на экспериментаторах, собиравших, настраивавших и работающих на этой установке. Они прилагают все усилия для того, чтобы, во-первых, корректно определить эти погрешности, а во-вторых, их минимизировать. Собственно, они этим начинают заниматься с самых первых дней работы установки, даже когда еще собственно научная программа исследований и не началась.

Возможные источники систематических погрешностей

Современный коллайдерный эксперимент очень сложен. В нём есть место огромному количеству источников систематических погрешностей на самых разных стадиях получения экспериментального результата. Вот некоторые из них.

Погрешности могут возникать на уровне «железа», при получении сырых данных:

- дефектные или неработающие отдельные регистрирующие компоненты или считывающие элементы. В детекторе миллионы отдельных компонентов, и даже если 1% из них оказался дефектным, это может ухудшить «зоркость» детектора и четкость регистрации сигналов. Надо подчеркнуть, что, даже если при запуске детектор работает на все 100%, постоянное детектирование частиц (это же жесткая радиация!) с течением времени выводит из строя отдельные компоненты, так что следить за поведением детектора абсолютно необходимо;

- наличие «слепых зон» детектора; например, если частица вылетает близко к оси пучков, то она улетит в трубу и детектор ее просто не заметит.

Погрешности могут возникать на этапе распознавания сырых данных и их превращение в физическое событие:

- погрешность при измерении энергии частиц в калориметре;

- погрешность при измерении траектории частиц в трековых детекторах, из-за которой неточно измеряется точка вылета и импульс частицы;

- неправильная идентификация типа частицы (например, система неудачно распознала след от π-мезона и приняла его за K-мезон). Более тонкий вариант: неправильное объединение адронов в одну адронную струю и неправильная оценка ее энергии;

- неправильный подсчет числа частиц (две частицы случайно вылетели так близко друг к другу, что детектор «увидел» только один след и посчитал их за одну).

Наконец, новые систематические погрешности добавляются на этапе позднего анализа события:

- неточность в измерении светимости пучков, которая влияет на пересчет числа событий в сечение процесса;

- наличие посторонних процессов рождения частиц, которые отличаются с физической точки зрения, но, к сожалению, выглядят для детектора одинаковыми. Такие процессы порождают неустранимый фон, который часто мешает разглядеть искомый эффект;

- необходимость моделировать процессы (в особенности, адронизацию, превращение кварков в адроны), опираясь частично на теорию, частично на прошлые эксперименты. Несовершенство того и другого привносит неточности и в новый экспериментальный результат. По этой причине теоретическую погрешность тоже часто относят к систематике.

В отдельных случаях встречаются источники систематических погрешностей, которые умудряются попасть сразу во все категории, они совмещают в себе и свойства детекторного «железа», и методы обработки и интерпретации данных. Например, если вы хотите сравнить друг с другом количество рожденных частиц и античастиц какого-то сорта (например, мюонов и антимюонов), то вам не стоит забывать, что ваш детектор состоит из вещества, а не из антивещества! Этот «перекос» в сторону вещества может привести к тому, что детектор будет видеть мюонов меньше, чем антимюонов, подробности см. в заметке Немножко про CP-нарушение, или Как жаль, что у нас нет детекторов из антивещества!.

Всю эту прорву источников потенциальных проблем надо распознать и оценить их влияние на выполняемый анализ. Здесь никаких абсолютно универсальных алгоритмов нет; исследователь должен сам понять, на какие погрешности надо обращать внимание и как грамотно их оценить. Конечно, тут на помощь приходят разные калибровочные измерения, выполненные в первые год-два работы детектора, и программы моделирования, которые позволяют виртуально протестировать поведение детектора в тех или иных условиях. Но главным в этом искусстве всё же является физическое чутье экспериментатора, его квалификация и накопленный опыт.

Почему важна грамотная оценка систематики

Беспечная оценка систематических погрешностей может привести к двум крайностям, причем обе очень нежелательны.

Заниженная погрешность — то есть неоправданная уверенность экспериментатора в том, что погрешности в его детекторе маленькие, хотя они на самом деле намного больше, — исключительно опасна, поскольку она может привести к совершенно неправильным научным выводам. Например, экспериментатор может на их основании решить, что измерения отличаются от теоретических предсказаний на уровне статистической значимости 10 стандартных отклонений (сенсация!), хотя истинная причина расхождения может просто состоять в том, что он проглядел источник ошибок, в 10 раз увеличивающий неопределенность измерения, и никакого расхождения на самом деле нет.

В борьбе с этой опасностью есть соблазн впасть в другую крайность: «А вдруг там есть еще какие-то погрешности? Может, я что-то не учел? Давай-ка я на всякий случай увеличу погрешности измерения в 10 раз для пущей безопасности.» Такая крайность плоха тем, что она обессмысливает измерение. Неоправданно завышая погрешность, вы рискуете получить результат, который будет, конечно, правильным, но очень неопределенным, ничем не лучше тех результатов, которые уже были получены до вас на гораздо более скромных установках. Такой подход, фактически, перечеркивает всю работу по разработке технологий, по изготовлению компонентов, по сборке детектора, все затраты на его работу и на анализ результатов.

Грамотный и ответственный анализ систематики должен удерживать оптимальный баланс (максимальная достоверность при максимальной научной ценности), не допуская таких крайностей. Это очень тонкая и сложная работа, и первые страницы в большинстве современных экспериментальных статей по физике частиц посвящены тщательному обсуждению систематических (а также статистических) погрешностей.

Мы не будем обсуждать подробности того, как обсчитывать систематические погрешности. Подчеркнем только, что это серьезная наука с множеством тонкостей и подводных камней. В качестве примера умеренно простого обсуждения некоторых вопросов см. статью Systematic Errors: facts and fictions.

Систематические погрешности при повторных измерениях остаются постоянными или изменяются по определенному закону.

Когда судят о погрешности, подразумевают не значение, а интервал значений, в котором с заданной вероятностью находится истинное значение. Поэтому говорят об оценке погрешности. Если бы погрешность оказалась измеренной, т.е. стали бы известны её знак и значение, то её можно было бы исключить из действительного значения измеряемой физической величины и получить истинное значение.

Для получения результатов, минимально отличающихся от истинного значения измеряемой физической величины, проводят многократные наблюдения и проводят математическую обработку полученного массива с целью определения и минимизации случайной составляющей погрешности.

Минимизация систематической погрешности в процессе наблюдений выполняется следующими методами: метод замещения (состоит в замещении измеряемой величины мерой), метод противопоставления (состоит в двух поочерёдных измерениях при замене местами меры и измеряемого объекта), метод компенсации погрешности по знаку (состоит в двух поочерёдных измерениях, при которых влияющая величина становится противоположной).

При многократных наблюдениях возможно апостериорное (после выполнения наблюдений) исключение систематической погрешности в результате анализа рядов наблюдений. Рассмотрим графический анализ. При этом результаты последовательных наблюдений представляются функцией времени либо ранжируются в порядке возрастания погрешности.

Рассмотрим временную зависимость. Будем проводить наблюдения через одинаковые интервалы времени. Результаты последовательных наблюдений являются случайной функцией времени. В серии экспериментов, состоящих из ряда последовательных наблюдений, получаем одну реализацию этой функции. При повторении серии получаем новую реализацию, отличающуюся от первой.

Реализации отличаются преимущественно из-за влияния факторов, определяющих случайную погрешность, а факторы, определяющие систематическую погрешность, одинаково проявляются для соответствующих моментов времени в каждой реализации. Значение, соответствующее каждому моменту времени, называется сечением случайной функции времени. Для каждого сечения можно найти среднее по всем реализациям значение. Очевидно, что эта составляющая и определяет систематическую погрешность. Если через значения систематической погрешности для всех моментов времени провести плавную кривую, то она будет характеризовать временную закономерность изменения погрешности. Зная закономерность изменения, можем определить поправку для исключения систематической погрешности. После исключения систематической погрешности получаем «исправленный ряд результатов наблюдений».

Известен ряд способов исключения систематических погрешностей, которые условно можно разделить па 4 основные группы:

- устранение источников погрешностей до начала измерений;

- исключение почетностей в процессе измерения способами замещения, компенсации погрешностей по знаку, противопоставления, симметричных наблюдений;

- внесение известных поправок в результат измерения (исключение погрешностей начислением);

- оценка границ систематических погрешностей, если их нельзя исключить.

По характеру проявления систематические погрешности подразделяют на постоянные, прогрессивные и периодические.

Постоянные систематические погрешности сохраняют свое значение в течение всего времени измерений (например, погрешность в градуировке шкалы прибора переносится на все результаты измерений).

Прогрессивные погрешности – погрешности, которые в процессе измерении подрастают или убывают (например, погрешности, возникающие вследствие износа контактирующих деталей средств измерения).

И группу систематических погрешностей можно отнести: инструментальные погрешности; погрешности из-за неправильной установки измерительного устройства; погрешности, возникающие вследствие внешних влияний; погрешности метода измерения (теоретические погрешности); субъективные погрешности.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Systematic bias» redirects here. For the sociological and organizational phenomenon, see Systemic bias.

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.[1] In statistics, an error is not necessarily a «mistake». Variability is an inherent part of the results of measurements and of the measurement process.

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random and systematic.[2]

Random errors are errors in measurement that lead to measurable values being inconsistent when repeated measurements of a constant attribute or quantity are taken. Systematic errors are errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by repeatable processes inherent to the system.[3] Systematic error may also refer to an error with a non-zero mean, the effect of which is not reduced when observations are averaged.[citation needed]

Measurement errors can be summarized in terms of accuracy and precision.

Measurement error should not be confused with measurement uncertainty.

Science and experiments[edit]

When either randomness or uncertainty modeled by probability theory is attributed to such errors, they are «errors» in the sense in which that term is used in statistics; see errors and residuals in statistics.

Every time we repeat a measurement with a sensitive instrument, we obtain slightly different results. The common statistical model used is that the error has two additive parts:

- Systematic error which always occurs, with the same value, when we use the instrument in the same way and in the same case.

- Random error which may vary from observation to another.

Systematic error is sometimes called statistical bias. It may often be reduced with standardized procedures. Part of the learning process in the various sciences is learning how to use standard instruments and protocols so as to minimize systematic error.

Random error (or random variation) is due to factors that cannot or will not be controlled. One possible reason to forgo controlling for these random errors is that it may be too expensive to control them each time the experiment is conducted or the measurements are made. Other reasons may be that whatever we are trying to measure is changing in time (see dynamic models), or is fundamentally probabilistic (as is the case in quantum mechanics — see Measurement in quantum mechanics). Random error often occurs when instruments are pushed to the extremes of their operating limits. For example, it is common for digital balances to exhibit random error in their least significant digit. Three measurements of a single object might read something like 0.9111g, 0.9110g, and 0.9112g.

Characterization[edit]

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random error and systematic error.[2]

Random error is always present in a measurement. It is caused by inherently unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading. Random errors show up as different results for ostensibly the same repeated measurement. They can be estimated by comparing multiple measurements and reduced by averaging multiple measurements.

Systematic error is predictable and typically constant or proportional to the true value. If the cause of the systematic error can be identified, then it usually can be eliminated. Systematic errors are caused by imperfect calibration of measurement instruments or imperfect methods of observation, or interference of the environment with the measurement process, and always affect the results of an experiment in a predictable direction. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

The Performance Test Standard PTC 19.1-2005 “Test Uncertainty”, published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), discusses systematic and random errors in considerable detail. In fact, it conceptualizes its basic uncertainty categories in these terms.

Random error can be caused by unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus, or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading; these fluctuations may be in part due to interference of the environment with the measurement process. The concept of random error is closely related to the concept of precision. The higher the precision of a measurement instrument, the smaller the variability (standard deviation) of the fluctuations in its readings.

Sources[edit]

Sources of systematic error[edit]

Imperfect calibration[edit]

Sources of systematic error may be imperfect calibration of measurement instruments (zero error), changes in the environment which interfere with the measurement process and sometimes imperfect methods of observation can be either zero error or percentage error. If you consider an experimenter taking a reading of the time period of a pendulum swinging past a fiducial marker: If their stop-watch or timer starts with 1 second on the clock then all of their results will be off by 1 second (zero error). If the experimenter repeats this experiment twenty times (starting at 1 second each time), then there will be a percentage error in the calculated average of their results; the final result will be slightly larger than the true period.

Distance measured by radar will be systematically overestimated if the slight slowing down of the waves in air is not accounted for. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

Systematic errors may also be present in the result of an estimate based upon a mathematical model or physical law. For instance, the estimated oscillation frequency of a pendulum will be systematically in error if slight movement of the support is not accounted for.

Quantity[edit]

Systematic errors can be either constant, or related (e.g. proportional or a percentage) to the actual value of the measured quantity, or even to the value of a different quantity (the reading of a ruler can be affected by environmental temperature). When it is constant, it is simply due to incorrect zeroing of the instrument. When it is not constant, it can change its sign. For instance, if a thermometer is affected by a proportional systematic error equal to 2% of the actual temperature, and the actual temperature is 200°, 0°, or −100°, the measured temperature will be 204° (systematic error = +4°), 0° (null systematic error) or −102° (systematic error = −2°), respectively. Thus the temperature will be overestimated when it will be above zero and underestimated when it will be below zero.

Drift[edit]

Systematic errors which change during an experiment (drift) are easier to detect. Measurements indicate trends with time rather than varying randomly about a mean. Drift is evident if a measurement of a constant quantity is repeated several times and the measurements drift one way during the experiment. If the next measurement is higher than the previous measurement as may occur if an instrument becomes warmer during the experiment then the measured quantity is variable and it is possible to detect a drift by checking the zero reading during the experiment as well as at the start of the experiment (indeed, the zero reading is a measurement of a constant quantity). If the zero reading is consistently above or below zero, a systematic error is present. If this cannot be eliminated, potentially by resetting the instrument immediately before the experiment then it needs to be allowed by subtracting its (possibly time-varying) value from the readings, and by taking it into account while assessing the accuracy of the measurement.

If no pattern in a series of repeated measurements is evident, the presence of fixed systematic errors can only be found if the measurements are checked, either by measuring a known quantity or by comparing the readings with readings made using a different apparatus, known to be more accurate. For example, if you think of the timing of a pendulum using an accurate stopwatch several times you are given readings randomly distributed about the mean. Hopings systematic error is present if the stopwatch is checked against the ‘speaking clock’ of the telephone system and found to be running slow or fast. Clearly, the pendulum timings need to be corrected according to how fast or slow the stopwatch was found to be running.

Measuring instruments such as ammeters and voltmeters need to be checked periodically against known standards.

Systematic errors can also be detected by measuring already known quantities. For example, a spectrometer fitted with a diffraction grating may be checked by using it to measure the wavelength of the D-lines of the sodium electromagnetic spectrum which are at 600 nm and 589.6 nm. The measurements may be used to determine the number of lines per millimetre of the diffraction grating, which can then be used to measure the wavelength of any other spectral line.

Constant systematic errors are very difficult to deal with as their effects are only observable if they can be removed. Such errors cannot be removed by repeating measurements or averaging large numbers of results. A common method to remove systematic error is through calibration of the measurement instrument.

Sources of random error[edit]

The random or stochastic error in a measurement is the error that is random from one measurement to the next. Stochastic errors tend to be normally distributed when the stochastic error is the sum of many independent random errors because of the central limit theorem. Stochastic errors added to a regression equation account for the variation in Y that cannot be explained by the included Xs.

Surveys[edit]

The term «observational error» is also sometimes used to refer to response errors and some other types of non-sampling error.[1] In survey-type situations, these errors can be mistakes in the collection of data, including both the incorrect recording of a response and the correct recording of a respondent’s inaccurate response. These sources of non-sampling error are discussed in Salant and Dillman (1994) and Bland and Altman (1996).[4][5]

These errors can be random or systematic. Random errors are caused by unintended mistakes by respondents, interviewers and/or coders. Systematic error can occur if there is a systematic reaction of the respondents to the method used to formulate the survey question. Thus, the exact formulation of a survey question is crucial, since it affects the level of measurement error.[6] Different tools are available for the researchers to help them decide about this exact formulation of their questions, for instance estimating the quality of a question using MTMM experiments. This information about the quality can also be used in order to correct for measurement error.[7][8]

Effect on regression analysis[edit]

If the dependent variable in a regression is measured with error, regression analysis and associated hypothesis testing are unaffected, except that the R2 will be lower than it would be with perfect measurement.

However, if one or more independent variables is measured with error, then the regression coefficients and standard hypothesis tests are invalid.[9]: p. 187 This is known as attenuation bias.[10]

See also[edit]

- Bias (statistics)

- Cognitive bias

- Correction for measurement error (for Pearson correlations)

- Errors and residuals in statistics

- Error

- Replication (statistics)

- Statistical theory

- Metrology

- Regression dilution

- Test method

- Propagation of uncertainty

- Instrument error

- Measurement uncertainty

- Errors-in-variables models

- Systemic bias

References[edit]

- ^ a b Dodge, Y. (2003) The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms, OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-920613-1

- ^ a b John Robert Taylor (1999). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books. p. 94, §4.1. ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0.

- ^ «Systematic error». Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Salant, P.; Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your survey. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01273-4.

- ^ Bland, J. Martin; Altman, Douglas G. (1996). «Statistics Notes: Measurement Error». BMJ. 313 (7059): 744. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7059.744. PMC 2352101. PMID 8819450.

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, Evaluation and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research (Second ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-63461-5.

- ^ DeCastellarnau, A. and Saris, W. E. (2014). A simple procedure to correct for measurement errors in survey research. European Social Survey Education Net (ESS EduNet). Available at: http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/measurement Archived 2019-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Revilla, M. (2015). «Correction for measurement errors in survey research: necessary and possible» (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 127 (3): 1005–1020. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1002-x. hdl:10230/28341. S2CID 146550566.

- ^ Hayashi, Fumio (2000). Econometrics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01018-2.

- ^ Angrist, Joshua David; Pischke, Jörn-Steffen (2015). Mastering ‘metrics : the path from cause to effect. Princeton, New Jersey. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-691-15283-7. OCLC 877846199.

The bias generated by this sort of measurement error in regressors is called attenuation bias.

Further reading[edit]

- Cochran, W. G. (1968). «Errors of Measurement in Statistics». Technometrics. 10 (4): 637–666. doi:10.2307/1267450. JSTOR 1267450.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Systematic bias» redirects here. For the sociological and organizational phenomenon, see Systemic bias.

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.[1] In statistics, an error is not necessarily a «mistake». Variability is an inherent part of the results of measurements and of the measurement process.

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random and systematic.[2]

Random errors are errors in measurement that lead to measurable values being inconsistent when repeated measurements of a constant attribute or quantity are taken. Systematic errors are errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by repeatable processes inherent to the system.[3] Systematic error may also refer to an error with a non-zero mean, the effect of which is not reduced when observations are averaged.[citation needed]

Measurement errors can be summarized in terms of accuracy and precision.

Measurement error should not be confused with measurement uncertainty.

Science and experiments[edit]

When either randomness or uncertainty modeled by probability theory is attributed to such errors, they are «errors» in the sense in which that term is used in statistics; see errors and residuals in statistics.

Every time we repeat a measurement with a sensitive instrument, we obtain slightly different results. The common statistical model used is that the error has two additive parts:

- Systematic error which always occurs, with the same value, when we use the instrument in the same way and in the same case.

- Random error which may vary from observation to another.

Systematic error is sometimes called statistical bias. It may often be reduced with standardized procedures. Part of the learning process in the various sciences is learning how to use standard instruments and protocols so as to minimize systematic error.

Random error (or random variation) is due to factors that cannot or will not be controlled. One possible reason to forgo controlling for these random errors is that it may be too expensive to control them each time the experiment is conducted or the measurements are made. Other reasons may be that whatever we are trying to measure is changing in time (see dynamic models), or is fundamentally probabilistic (as is the case in quantum mechanics — see Measurement in quantum mechanics). Random error often occurs when instruments are pushed to the extremes of their operating limits. For example, it is common for digital balances to exhibit random error in their least significant digit. Three measurements of a single object might read something like 0.9111g, 0.9110g, and 0.9112g.

Characterization[edit]

Measurement errors can be divided into two components: random error and systematic error.[2]

Random error is always present in a measurement. It is caused by inherently unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading. Random errors show up as different results for ostensibly the same repeated measurement. They can be estimated by comparing multiple measurements and reduced by averaging multiple measurements.

Systematic error is predictable and typically constant or proportional to the true value. If the cause of the systematic error can be identified, then it usually can be eliminated. Systematic errors are caused by imperfect calibration of measurement instruments or imperfect methods of observation, or interference of the environment with the measurement process, and always affect the results of an experiment in a predictable direction. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

The Performance Test Standard PTC 19.1-2005 “Test Uncertainty”, published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), discusses systematic and random errors in considerable detail. In fact, it conceptualizes its basic uncertainty categories in these terms.

Random error can be caused by unpredictable fluctuations in the readings of a measurement apparatus, or in the experimenter’s interpretation of the instrumental reading; these fluctuations may be in part due to interference of the environment with the measurement process. The concept of random error is closely related to the concept of precision. The higher the precision of a measurement instrument, the smaller the variability (standard deviation) of the fluctuations in its readings.

Sources[edit]

Sources of systematic error[edit]

Imperfect calibration[edit]

Sources of systematic error may be imperfect calibration of measurement instruments (zero error), changes in the environment which interfere with the measurement process and sometimes imperfect methods of observation can be either zero error or percentage error. If you consider an experimenter taking a reading of the time period of a pendulum swinging past a fiducial marker: If their stop-watch or timer starts with 1 second on the clock then all of their results will be off by 1 second (zero error). If the experimenter repeats this experiment twenty times (starting at 1 second each time), then there will be a percentage error in the calculated average of their results; the final result will be slightly larger than the true period.

Distance measured by radar will be systematically overestimated if the slight slowing down of the waves in air is not accounted for. Incorrect zeroing of an instrument leading to a zero error is an example of systematic error in instrumentation.

Systematic errors may also be present in the result of an estimate based upon a mathematical model or physical law. For instance, the estimated oscillation frequency of a pendulum will be systematically in error if slight movement of the support is not accounted for.

Quantity[edit]

Systematic errors can be either constant, or related (e.g. proportional or a percentage) to the actual value of the measured quantity, or even to the value of a different quantity (the reading of a ruler can be affected by environmental temperature). When it is constant, it is simply due to incorrect zeroing of the instrument. When it is not constant, it can change its sign. For instance, if a thermometer is affected by a proportional systematic error equal to 2% of the actual temperature, and the actual temperature is 200°, 0°, or −100°, the measured temperature will be 204° (systematic error = +4°), 0° (null systematic error) or −102° (systematic error = −2°), respectively. Thus the temperature will be overestimated when it will be above zero and underestimated when it will be below zero.

Drift[edit]

Systematic errors which change during an experiment (drift) are easier to detect. Measurements indicate trends with time rather than varying randomly about a mean. Drift is evident if a measurement of a constant quantity is repeated several times and the measurements drift one way during the experiment. If the next measurement is higher than the previous measurement as may occur if an instrument becomes warmer during the experiment then the measured quantity is variable and it is possible to detect a drift by checking the zero reading during the experiment as well as at the start of the experiment (indeed, the zero reading is a measurement of a constant quantity). If the zero reading is consistently above or below zero, a systematic error is present. If this cannot be eliminated, potentially by resetting the instrument immediately before the experiment then it needs to be allowed by subtracting its (possibly time-varying) value from the readings, and by taking it into account while assessing the accuracy of the measurement.

If no pattern in a series of repeated measurements is evident, the presence of fixed systematic errors can only be found if the measurements are checked, either by measuring a known quantity or by comparing the readings with readings made using a different apparatus, known to be more accurate. For example, if you think of the timing of a pendulum using an accurate stopwatch several times you are given readings randomly distributed about the mean. Hopings systematic error is present if the stopwatch is checked against the ‘speaking clock’ of the telephone system and found to be running slow or fast. Clearly, the pendulum timings need to be corrected according to how fast or slow the stopwatch was found to be running.

Measuring instruments such as ammeters and voltmeters need to be checked periodically against known standards.

Systematic errors can also be detected by measuring already known quantities. For example, a spectrometer fitted with a diffraction grating may be checked by using it to measure the wavelength of the D-lines of the sodium electromagnetic spectrum which are at 600 nm and 589.6 nm. The measurements may be used to determine the number of lines per millimetre of the diffraction grating, which can then be used to measure the wavelength of any other spectral line.

Constant systematic errors are very difficult to deal with as their effects are only observable if they can be removed. Such errors cannot be removed by repeating measurements or averaging large numbers of results. A common method to remove systematic error is through calibration of the measurement instrument.

Sources of random error[edit]

The random or stochastic error in a measurement is the error that is random from one measurement to the next. Stochastic errors tend to be normally distributed when the stochastic error is the sum of many independent random errors because of the central limit theorem. Stochastic errors added to a regression equation account for the variation in Y that cannot be explained by the included Xs.

Surveys[edit]

The term «observational error» is also sometimes used to refer to response errors and some other types of non-sampling error.[1] In survey-type situations, these errors can be mistakes in the collection of data, including both the incorrect recording of a response and the correct recording of a respondent’s inaccurate response. These sources of non-sampling error are discussed in Salant and Dillman (1994) and Bland and Altman (1996).[4][5]

These errors can be random or systematic. Random errors are caused by unintended mistakes by respondents, interviewers and/or coders. Systematic error can occur if there is a systematic reaction of the respondents to the method used to formulate the survey question. Thus, the exact formulation of a survey question is crucial, since it affects the level of measurement error.[6] Different tools are available for the researchers to help them decide about this exact formulation of their questions, for instance estimating the quality of a question using MTMM experiments. This information about the quality can also be used in order to correct for measurement error.[7][8]

Effect on regression analysis[edit]

If the dependent variable in a regression is measured with error, regression analysis and associated hypothesis testing are unaffected, except that the R2 will be lower than it would be with perfect measurement.

However, if one or more independent variables is measured with error, then the regression coefficients and standard hypothesis tests are invalid.[9]: p. 187 This is known as attenuation bias.[10]

See also[edit]

- Bias (statistics)

- Cognitive bias

- Correction for measurement error (for Pearson correlations)

- Errors and residuals in statistics

- Error

- Replication (statistics)

- Statistical theory

- Metrology

- Regression dilution

- Test method

- Propagation of uncertainty

- Instrument error

- Measurement uncertainty

- Errors-in-variables models

- Systemic bias

References[edit]

- ^ a b Dodge, Y. (2003) The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms, OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-920613-1

- ^ a b John Robert Taylor (1999). An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. University Science Books. p. 94, §4.1. ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0.

- ^ «Systematic error». Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Salant, P.; Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your survey. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01273-4.

- ^ Bland, J. Martin; Altman, Douglas G. (1996). «Statistics Notes: Measurement Error». BMJ. 313 (7059): 744. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7059.744. PMC 2352101. PMID 8819450.

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, Evaluation and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research (Second ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-63461-5.

- ^ DeCastellarnau, A. and Saris, W. E. (2014). A simple procedure to correct for measurement errors in survey research. European Social Survey Education Net (ESS EduNet). Available at: http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/measurement Archived 2019-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saris, W. E.; Revilla, M. (2015). «Correction for measurement errors in survey research: necessary and possible» (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 127 (3): 1005–1020. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1002-x. hdl:10230/28341. S2CID 146550566.

- ^ Hayashi, Fumio (2000). Econometrics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01018-2.

- ^ Angrist, Joshua David; Pischke, Jörn-Steffen (2015). Mastering ‘metrics : the path from cause to effect. Princeton, New Jersey. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-691-15283-7. OCLC 877846199.

The bias generated by this sort of measurement error in regressors is called attenuation bias.

Further reading[edit]

- Cochran, W. G. (1968). «Errors of Measurement in Statistics». Technometrics. 10 (4): 637–666. doi:10.2307/1267450. JSTOR 1267450.

7.1 Систематические погрешности и их классификация

Систематическая погрешность

считается специфической, «вырожденной»

случайной величиной, обладающей

некоторыми, но не всеми свойствами

случайной величины, изучаемой в теории

вероятностей и математической статистике.

Свойства систематической погрешности,

которые необходимо учитывать при

объединении составляющих погрешности,

отражаются такими же характеристиками,

что и свойства «настоящих» случайных

величин – дисперсией

(СКО) и коэффициентом взаимной корреляции.

Систематическая погрешность представляет

собой определенную функцию влияющих

факторов, состав которых зависит от

физических, конструктивных и

технологических особенностей СИ,

условий их применения, а также

индивидуальных качеств наблюдателя.

В метрологической практике при оценке

систематических погрешностей должно

учитываться влияние следующих основных

факторов:

1. Объект

измерения. Перед

измерением он должен быть достаточно

хорошо изучен с целью корректного выбора

его модели. Чем полнее модель соответствует

исследуемому объекту, тем точнее могут

быть получены результаты измерения.

Например, кривизна земной поверхности

может не учитываться при измерении

площади сельскохозяйственных угодий,

так как она не вносит ощутимой погрешности,

однако при измерении площади океанов

ею пренебрегать уже нельзя.

2. Субъект

измерения. Его вклад

в погрешность измерения необходимо

уменьшать путем подбора операторов

высокой квалификации и соблюдения

требований эргономики при разработке

СИ.

3. Метод

и средство измерений.

Чрезвычайно важен их правильный

выбор, который производится на основе

априорной информации об объекте

измерения. Чем больше априорной

информации, тем точнее может быть

проведено измерение. Основной вклад в

систематическую погрешность вносит,

как правило, методическая погрешность.

4. Условия

измерения. Обеспечение

и стабилизация нормальных условий

являются необходимыми требованиями

для минимизации дополнительной

погрешности, которая по своей природе,

как правило, является систематической.

Систематические погрешности

принято классифицировать по двум

признакам. По характеру

изменения во времени

они делятся на

постоянные и переменные.

Постоянными

называются такие

погрешности измерения, которые

остаются неизменными в течение всей

серии измерений. Например, погрешность

от того, что неправильно установлен

ноль стрелочного электроизмерительного

прибора, погрешность от постоянного

дополнительного веса на чашке весов и

т.д.

Переменными

называются погрешности,

изменяющиеся в процессе измерения.

Они делятся на монотонно изменяющиеся,

периодические и изменяющиеся по сложному

закону.

Если в процессе измерения

систематическая погрешность монотонно

возрастает или убывает, ее называют

монотонно изменяющейся.

Например, она имеет

место при постепенном разряде батареи,

питающей средство измерений.

Периодической

называется погрешность,

значение которой является периодической

функцией времени. Примером может

служить погрешность, обусловленная

суточными колебаниями напряжения

силовой питающей сети, температуры

окружающей среды и др. Систематические

погрешности могут изменяться и по более

сложному закону, обусловленному

какими-либо внешними причинами.

По причинам

возникновения

погрешности делятся

на методические,

инструментальные и

личные

(субъективные).

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Systematic error occurs when an observed or calculated value deviates from the true value in a consistent way.

From: Woven Textiles, 2012

Experimental techniques

Yanqiu Huang, … Zhixiang Cao, in Industrial Ventilation Design Guidebook (Second Edition), 2021

4.3.3.2 Measurement errors

The measurement errors are divided into two categories: systematic errors and random errors (OIML, 1978).

Systematic error is an error which, in the course of a number of measurements carried out under the same conditions of a given value and quantity, either remains constant in absolute value and sign, or varies according to definite law with changing conditions.

Random error varies in an unpredictable manner in absolute value and in sign when a large number of measurements of the same value of a quantity are made under essentially identical conditions.

The origins of the above two errors are different in cause and nature. A simple example is when the mass of a weight is less than its nominal value, a systematic error occurs, which is constant in absolute value and sign. This is a pure systematic error. A ventilation-related example is when the instrument factor of a Pitot-static tube, which defines the relationship between the measured pressure difference and the velocity, is incorrect, a systematic error occurs. On the other hand, if a Pitot-static tube is positioned manually in a duct in such a way that the tube tip is randomly on either side of the intended measurement point, a random error occurs. This way, different phenomena create different types of error. The (total) error of measurement usually is a combination of the above two types.

The question may be asked, that is, what is the reason for dividing the errors into two categories? The answer is the totally different way of dealing with these different types. Systematic error can be eliminated to a sufficient degree, whereas random error cannot. The following section shows how to deal with these errors.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128166734000043

EXPERIMENTAL TECHNIQUES

KAI SIREN, … PETER V. NIELSEN, in Industrial Ventilation Design Guidebook, 2001

12.3.3.11 Systematic Errors

Systematic error, as stated above, can be eliminated—not totally, but usually to a sufficient degree. This elimination process is called “calibration.” Calibration is simply a procedure where the result of measurement recorded by an instrument is compared with the measurement result of a standard. A standard is a measuring device intended to define, to represent physically, to conserve, or to reproduce the unit of measurement in order to transmit it to other measuring instruments by comparison.1 There are several categories of standards, but, simplifying a little, a standard is an instrument with a very high accuracy and can for that reason be used as a reference for ordinary measuring instruments. The calibration itself is usually carried out by measuring the quantity over the whole range required and by defining either one correction factor for the whole range, for a constant systematic error, or a correction curve or equation for the whole range. Applying this correction to the measurement result eliminates, more or less, the systematic error and gives the corrected result of measurement.

A primary standard has the highest metrological quality in a given field. Hence, the primary standard is the most accurate way to measure or to reproduce the value of a quantity. Primary standards are usually complicated instruments, which are essentially laboratory instruments and unsuited for site measurement. They require skilled handling and can be expensive. For these reasons it is not practical to calibrate all ordinary meters against a primary standard. To utilize the solid metrological basis of the primary standard, a chain of secondary standards, reference standards, and working standards combine the primary standard and the ordinary instruments. The lower level standard in the chain is calibrated using the next higher level standard. This is called “traceability.” In all calibrations traceability along the chain should exist, up to the instrument with the highest reliability, the primary standard.

The question is often asked, How often should calibration be carried out? Is it sufficient to do it once, or should it be repeated? The answer to this question depends on the instrument type. A very simple instrument that is robust and stable may require calibrating only once during its lifetime. Some fundamental meters do not need calibration at all. A Pitot-static tube or a liquid U-tube manometer are examples of such simple instruments. On the other hand, complicated instruments with many components or sensitive components may need calibration at short intervals. Also fouling and wearing are reasons not only for maintenance but also calibration. Thus the proper calibration interval depends on the instrument itself and its use. The manufacturers recommendations as well as past experience are often the only guidelines.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780122896767500151

Intelligent control and protection in the Russian electric power system

Nikolai Voropai, … Daniil Panasetsky, in Application of Smart Grid Technologies, 2018

3.3.1.2 Systematic errors in PMU measurements

The systematic errors caused by the errors of the instrument transformers that exceed the class of their accuracy are constantly present in the measurements and can be identified by considering some successive snapshots of measurements. The TE linearized at the point of a true measurement, taking into account random and systematic errors, can be written as:

(25)wky¯=∑l∈ωk∂w∂ylξyl+cyl=∑aklξyl+∑aklcyl

where ∑ aklξyl—mathematical expectation of random errors of the TE, equal to zero; ∑ aklcyl—mathematical expectation of systematic error of the TE, ωk—a set of measurements contained in the kth TE.

The author of Ref. [28] suggests an algorithm for the identification of a systematic component of the measurement error on the basis of the current discrepancy of the TE. The algorithm rests on the fact that systematic errors of measurements do not change through a long time interval. In this case, condition (17) will not be met during such an interval of time. Based on the snapshots that arrive at time instants 0, 1, 2, …, t − 1, t…, the sliding average method is used to calculate the mathematical expectation of the TE discrepancy:

(26)Δwkt=1−αΔwkt−1+αwkt

where 0 ≤ α ≤ 1.

Fig. 5 shows the curve of the TE discrepancy (a thin dotted line) calculated by (26) for 100 snapshots of measurements that do not have systematic errors.

Fig. 5. Detection of a systematic error in the PMU measurements and identification of mathematical expectation of the test equation.

It virtually does not exceed the threshold dk = 0.014 (a light horizontal line). Above the threshold, there is a curve of the TE discrepancy (a bold dotted line) that contains a measurement with a systematic error and a curve of nonzero mathematical expectation Δwk(t) ∈ [0.026; 0.03] (a black-blue thick line). However, the nonzero value of the calculated mathematical expectation of the TE discrepancy can only testify to the presence of a systematic error in the PMU measurements contained in this TE, but cannot be used to locate it.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128031285000039

Measurements

Sankara Papavinasam, in Corrosion Control in the Oil and Gas Industry, 2014

ii Systematic or determinate error

To define systematic error, one needs to understand ‘accuracy’. Accuracy is a measure of the closeness of the data to its true or accepted value. Figure 12.3 illustrates accuracy schematically.4 Determining the accuracy of a measurement is difficult because the true value may never be known, so for this reason an accepted value is commonly used. Systematic error moves the mean or average value of a measurement from the true or accepted value.

FIGURE 12.3. Difference between Accuracy and Precision in a Measurement.4

Reproduced with permission from Brooks/Cole, A Division of Cengage Learning.

Systematic error may be expressed as absolute error or relative error:

- •

-

The absolute error (EA) is a measure of the difference between the measured value (xi) and true or accepted value (xt) (Eqn. 12.5):

(Eqn. 12.5)EA=xi−xt

Absolute error bears a sign:

- •

-

A negative sign indicates that the measured value is smaller than true value and

- •

-

A positive sign indicates that the measured value is higher than true value

The relative error (ER) is the ratio of measured value to true value and it is expressed as (Eqn. 12.6):

(Eqn. 12.6)ER=(xi−xtxt).100

Table 12.2 illustrates the absolute and relative errors for six measurements in determining the concentration of 20 ppm of an ionic species in solution.

Table 12.2. Relative and Absolute Errors in Six Measurements of Aqueous Solution Containing 20 ppm of an Ionic Species

| Measured Value | Absolute Error | Relative Error (Percentage) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19.4 | −0.6 | −3.0 | Experimental value lower than actual value. |

| 19.5 | −0.5 | −2.5 | |

| 19.6 | −0.4 | −2.0 | |

| 19.8 | −0.2 | −1.0 | |

| 20.1 | +0.1 | +0.5 | Experimental value higher than actual value. |

| 20.3 | +0.3 | +1.5 |

Systematic error may occur due to instrument, methodology, and personal error.

Instrument error

Instrument error occurs due to variations that can affect the functionality of the instrument. Some common causes include temperature change, voltage fluctuation, variations in resistance, distortion of the container, error from original calibration, and contamination. Most instrument errors can be detected and corrected by frequently calibrating the instrument using a standard reference material. Standard reference materials may occur in different forms including minerals, gas mixtures, hydrocarbon mixtures, polymers, solutions of known concentration of chemicals, weight, and volume. The standard reference materials may be prepared in the laboratory or may be obtained from standard-making organizations (e.g., ASTM standard reference materials), government agencies (e.g., National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides about 900 reference materials) and commercial suppliers. If standard materials are not available, a blank test may be performed using a solution without the sample. The value from this test may be used to correct the results from the actual sample. However this methodology may not be applicable for correcting instrumental error in all situations.

Methodology error

Methodology error occurs due to the non-ideal physical or chemical behavior of the method. Some common causes include variation of chemical reaction and its rate, incompleteness of the reaction between analyte and the sensing element due to the presence of other interfering substances, non-specificity of the method, side reactions, and decomposition of the reactant due to the measurement process. Methodology error is often difficult to detect and correct, and is therefore the most serious of the three types of systematic error. Therefore a suitable method free from methodology error should be established for routine analysis.

Personal error

Personal error occurs due to carelessness, lack of detailed knowledge of the measurement, limitation (e.g., color blindness of a person performing color-change titration), judgment, and prejudice of person performing the measurement. Some of these can be overcome by automation, proper training, and making sure that the person overcomes any bias to preserve the integrity of the measurement.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123970220000121

Experimental Design and Sample Size Calculations

Andrew P. King, Robert J. Eckersley, in Statistics for Biomedical Engineers and Scientists, 2019

9.4.2 Blinding

Systematic errors can arise because either the participants or the researchers have particular knowledge about the experiment. Probably the best known example is the placebo effect, in which patients’ symptoms can improve simply because they believe that they have received some treatment even though, in reality, they have been given a treatment of no therapeutic value (e.g. a sugar pill). What is less well known, but nevertheless well established, is that the behavior of researchers can alter in a similar way. For example, a researcher who knows that a participant has received a specific treatment may monitor the participant much more carefully than a participant who he/she knows has received no treatment. Blinding is a method to reduce the chance of these effects causing a bias. There are three levels of blinding:

- 1.

-

Single-blind. The participant does not know if he/she is a member of the treatment or control group. This normally requires the control group to receive a placebo. Single-blinding can be easy to achieve in some types of experiments, for example, in drug trials the control group could receive sugar pills. However, it can be more difficult for other types of treatment. For example, in surgery there are ethical issues involved in patients having a placebo (or sham) operation.2

- 2.

-

Double-blind. Neither the participant nor the researcher who delivers the treatment knows whether the participant is in the treatment or control group.

- 3.

-

Triple-blind. Neither the participant, the researcher who delivers the treatment, nor the researcher who measures the response knows whether the participant is in the treatment or control group.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081029398000189

The pursuit and definition of accuracy

Anthony J. Martyr, David R. Rogers, in Engine Testing (Fifth Edition), 2021

Systematic instrument errors

Typical systematic errors (Fig. 19.2C) include the following:

- 1.

-

Zero errors—the instrument does not read zero when the value of the quantity observed is zero.

- 2.

-

Scaling errors—the instrument reads systematically high or low.

- 3.

-

Nonlinearity—the relation between the true value of the quantity and the indicated value is not exactly in proportion; if the proportion of error is plotted against each measurement over full scale, the graph is nonlinear.

- 4.

-

Dimensional errors—for example, the effective length of a dynamometer torque arm may not be precisely correct.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012821226400019X

Power spectrum and filtering

Andreas Skiadopoulos, Nick Stergiou, in Biomechanics and Gait Analysis, 2020

5.10 Practical implementation

As suggested by Winter (2009), to cancel the phase shift of the output signal relative to the input that is introduced by the second-order filter, the once-filtered data has to filtered again, but this time in the reverse direction. However, at every pass the −3dB cutoff frequency is pushed lower, and a correction is needed to match the original single-pass filter. This correction should be applied once the coefficients of the fourth-order low-pass filter are calculated. Nevertheless, it should be also checked whether functions of closed source software use the correction factor. If they have not used it, the output of the analyzed signal will be distorted. The format of the recursive second-order filter is given by Eq. (5.36) (Winter, 2009):

(5.36)yk=α0χk+α1χk−1+α2χk−2+β1yk−1+β2yk−2

where y are the filtered output data, x are past inputs, and k the kth sample.The coefficients α0,α1,α2,β1, and β2 for a second-order Butterworth low-pass filter are computed from Eq. (5.37) (Winter, 2009):

(5.37)ωc=tanπfcfsCK1=2ωcK2=ωc2K3=α1K2α0=K21+K1+K2α1=2α0α2=α0β1=K3−α1β2=1−α1-K3

where, ωc is the cutoff angular frequency in rad/s, fc is the cutoff frequency in Hz, and fs is the sampling rate in Hz. When the filtered data are filtered again in the reverse direction to cancel phase-shift, the following correction factor to compensate for the introduced error should be used:

(5.38)C=(21n−1)14

where n≥2 is the number of passes. For a single-pass C=1, and no compensation is needed. For a dual pass, (n=2), a compensation is needed, and the correction factor should be applied. Thus, the ωc term from Eq. (5.37) is calculated as follows:

(5.39)ωc=tan(πfcfs)(212−1)14=tan(πfcfs)0.802

A systematic error is introduced to the signal if the correction factor is not applied. Therefore, remember to check any algorithm before using it. Let us check the correctness of the fourth-order low-pass filter that was built previously in R language. Vignette 5.2 contains the code to perform Winter’s (2009) low-pass filter in R programming language. Because the filter needs two past inputs (two data points) to compute a present filtered output (one data point), the time-series data to be filtered (the raw data) should be padded at the beginning and at the end. Additional data are usually collected before and after the period of interest.

Vignette 5.2

The following vignette contains a code in R programming language that performs the fourth-order zero-phase-shift low-pass filter from Eq. (5.37).

- 1.

-

The first step is to create a sine (or equally a cosine) wave with known amplitude and known frequency. Vignette 5.3 is used to synthesize periodic digital waves. Let us create a simple periodic sine wave s[n] with the following characteristics:

- a.

-

Amplitude A=1 unit (e.g., 1 m);

- b.

-

Frequency f=2 Hz;

- c.

-

Phase θ=0 rad;

- d.

-

Shift a0=0 unit (e.g., 0 m).

Vignette 5.3

The following vignette contains a code in R programming language that synthesizes periodic waveforms from sinusoids.

Let us choose an arbitrary fundamental period T0=2 seconds, which corresponds to a fundamental frequency of f0=1/T0=0.5 Hz. Now, knowing the fundamental frequency, the fourth harmonic that corresponds to a sine wave with frequency of f=2 Hz will be chosen. The periodic sine wave s[n] will be sampled at Fs=40 Hz (Ts=1/40 seconds) (i.e., 20 times the Nyquist frequency, fN=2 Hz). The sine wave will be recorded for a time interval of t=2 s, which corresponds to N=80 data points. Thus, and because ω0=2πf0, we have:

s[n]=sin(2ω0nTs)

which means that the fourth harmonic has frequency f=2

Hz. Fig. 5.14A shows the sine wave created. The first and last 20 data points can be considered as extra points (padded). Additional data at the beginning and end of the signal are needed for the next steps because the filter is does not behave well at the edges. Thus, the signal of interest starts at 0.5

seconds and ends at 1.5

seconds, which corresponds to N=40 data points.

Figure 5.14. (A) Example of a low-pass filter (cutoff frequency=2 Hz) applied to a sine wave sampled at 40 Hz, with amplitude equal to 1 m, and frequency equal to 2 Hz. (B) The signal interpolated by a factor of 2, and filtered with cutoff frequency equal to the frequency of the sine wave (cutoff frequency=2 Hz). (C) Since the amplitude of the filtered signal has been reduced by a ratio of 0.707, the low-pass filter correctly attenuated the signal. The power spectra of the original and reconstructed signal are shown.

- 2.

-

An extra, but not mandatory, step is to interpolate the created sine wave in order to increase the temporal resolution of the created signal (Fig. 5.14B). Of course, when a digital periodic signal is created from scratch, like we are doing using the R code in the vignettes, we can easily sample the signal at higher frequencies. However, if we want to use real biomechanical time series data, that have already been collected, a possible way to increase its temporal resolution is by using the Whittaker–Shannon interpolation formula. With the Whittaker–Shannon interpolation a signal is up-sampled with interpolation using the sinc() function (Yaroslavsky, 1997):

(5.40)s(x)=∑n=0N−1αnsin(π(xΔx−n))Nsin(π(xΔx−n)/N)

The Whittaker–Shannon interpolation formula can be used to increase the temporal resolution after removing the “white” noise from the data. Without filtering, the interpolation results in a noise level equal to that of the original signal before sampling (Marks, 1991). However, the interpolation noise can be reduced by both oversampling and filtering the data before interpolation (Marks, 1991). An alternative, and efficient, method is to run the DFT, zero-pad the signal, and then take the IDFT to reconstruct it. Vignette 5.4 can be used to increase the temporal resolution by a factor of 2, which corresponds to a sampling frequency of 80 Hz.

Vignette 5.4

The following vignette contains a code in R programming language that runs the normalized discrete sinc() function, and the Whittaker–Shannon interpolation function.

- 3.

-